This is part two of our discussion of climate-smart landscapes, where we’ll dive into designing carbon sinks on your home landscape. Catch up on Part One, where we detail how carbon is sequestered and stored in the soil via a critical plant-microbe relationship. Below are our best practices for landscape designers when designing and maintaining a carbon net positive landscape.

Organic Soil Management

Organic soil management is an essential element of designing a carbon sink. As detailed in Part One of this blog series, CO2 sequestration and storage in the soil is governed by a diverse soil microbial community and their interactions with plants. To summarize: plants draw CO2 from the air and convert it into glucose via photosynthesis. The plant trades some of this sugar water for soil nutrients, broken down by microbes into a plant-available form. The exchange takes place on the roots, and microbes later exude a stable form of carbon called glomalin into the soil. Glomalin also aides in the formation of topsoil by aggregating soil particles.

This delicate and magical relationship is dependent upon both sides having something to give and something to take. Without the microbes, plants would never be able to access and breakdown all of the essential nutrients in the soil. Microbes depend on the plants for sugars and water to stay alive.

But, when this natural cycle is interrupted with inputs like synthetic fertilizers, the plant no longer needs nutrients from the microbes. Instead, the plant receives a flood of quick and easy NPK from the fertilizer. There is no need to exchange with the microbes, and there is no channel to store carbon in the soil. Soil microbes experience a brief surge in population from the nitrogen in the fertilizer; once the cheap food is consumed they target soil organic matter (carbon). Synthetic fertilizers not only disrupt the plant-microbe relationships, but they threaten to deplete organic matter significantly, rather than help store it.

This is why organic land care is of paramount importance for so many ecological reasons. By dousing our landscapes in chemicals, we are destroying one of our most valuable carbon sinks, one of the only natural systems for sequestering and stably storing a potent greenhouse gas. When designing carbon sinks, the landscape must be maintained organically.

Applying pesticides also indiscriminately kills insects, destroying habitat for essential pollinators, birds and beneficial insects. Learn more on our previous blog.

Minimize Disruption of Soil

Carbon stored in soil is relatively stable, especially around deeply-rooted plants, where it is stored in deeper layers of the soil strata. When soil is heavily disturbed and overturned however, the stored carbon is exposed to the air and released. This is why many regenerative farmers and landstewards now advocate for no-till farming and gardening. We avoid using roto-tillers whenever possible and suggest using hand tools to mix compost into top soil, for example. It is futile to design a carbon sink and not maintain it appropriately to keep the carbon stably stored.

Layered Plantings for Microbial Diversity, Plant Biomass

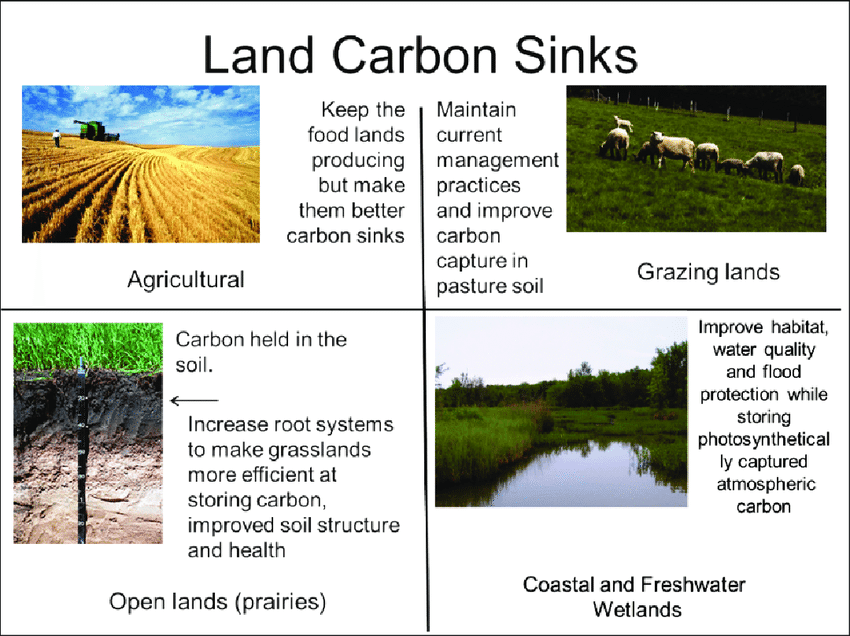

Layered plantings have long been a tenant of good garden design, but now we know the massive ecological value they bring as well. Simply put, the more plant diversity, the more soil microbe diversity, the bigger the underground network of carbon storage. There are billions of soil microbes in just a teaspoon of soil. Many microbes are specialists, adapted to only specific plants’ roots. Others are generalists, forming relationships with many types of plants. By designing diverse, varied and layered plantings, we are able to maximize the carbon exchange and storage. Diverse plantings have different root depths and occupy different spaces in the soil strata, maximizing where and how stably soil carbon can be stored. For example, prairie grasses are known to have some of the deepest roots, and greatest carbon storage capacity. Including woody plants – shrubs and trees—increases carbon storage in both the mychorrizal network and the woody biomass. Perennials are also valuable; each winter some of their root system dies off and contributes carbon to the soil. Clearly, a garden featuring trees, shrubs, grasses, and perennials has far more potential to sequester carbon than any one monoculture (ahem, lawn).

Minimize Maintenance Emissions

To reach carbon net positive landscapes, our sequestration must outpace our emissions. Ultimately, we need to eliminate landscape emissions whenever possible during installation and maintenance. Many of our clients utilize robotic electric mowing services for zero emission and zero effort maintenance. Our crews use electric leaf blowers and perform as many tasks by hand as possible. Synthetic fertilizers also indirectly increase emissions when they leach into water bodies, cause eutrophication and create anerobic environments where microbes feed on the organic matter and respire CO2, acidifying the water and threatening marine life.

Protect Coastal Wetlands

Connecticut, New York and New Jersey are blessed with ecological powerhouses: coastal wetlands. From marshes to mangroves, coastal wetlands can sequester and store ten times more carbon than a forest! As Hillary Stevens described as ELA keynote speaker, this is because of a few factors. 1) plants grow and photosynthesize very quickly in coastal wetlands 2) lack of oxygen inhibits decomposition of organic material that falls to the sea floor 3) salinity inhibits certain microbe populations that live in freshwater wetlands and decompose OM rapidly, emiting the potent greenhouse gas methane as a byproduct. This unique set of conditions makes coastal wetlands an incredible natural carbon sink that we must work to protect. Restoring natural tidal flows to areas of development / impoundment can have a measurable impact on CO2 sequestration.

We hope you enjoyed this post on how to designing carbon sinks and maintaining your landscape as a stable carbon sink. Our window for reversing a devastating path of climate change is closing and it is imperative to employ every method available for reducing CO2 in our atmosphere. Soil carbon storage has the potential to reduce atmospheric CO2 by thirty percent. We have the tools, will we act?

—

Green Jay Landscape Design

Where Design Meets Ecology

Contact us to schedule a consultation