Margaret Roach of the New York Times recently interviewed legendary entomologist Doug Tallamy for her article The Four Ecologically Crucial Things You Should Do in Your Garden. Tallamy is renowned for his book Bringing Nature Home, and his research at the University of Delaware on the interactions between insects and native plants, ultimately ranking a list of “keystone plants” as the top native selections to support biodiversity. Tallamy also started the non profit Homegrown National Park, which works to encourage homeowner adoption of ecological landscaping principals to create conservation corridors. In the recent article, Tallamy summarizes his research into four key objectives for homeowners to focus on in their landscape:

Every landscape needs to manage the watershed in which it lies. Every landscape needs to support pollinators. Every landscape needs to support a viable food web. And every landscape needs to sequester carbon.

We couldn’t agree more at Green Jay Landscape Design, in fact, it’s been Our Promise as ecological landscapers since our inception. Below we’ve outlined some tips and case studies for how we implement these four principles in residential landscapes across Westchester and Fairfield counties.

Manage Watersheds

Stormwater must be managed within property lines, and any waterbodies on site must be protected. Treating stormwater at the source, before it contaminates other waterbodies, is our best chance at keeping freshwater clean.

Achieving these goals can take many forms. At the most basic level, a home should have adequately sized gutters for the footprint of the home. Gutters should divert runoff from the roof at least 10 feet away from the house and into the landscape where it can be repurposed as passive irrigation and/or allowed to infiltrate into the groundwater.

If you have a particularly wet zone, consider planting a native plant rain garden above it to intercept the water and allow it to either return to the atmosphere via evapotranspiration or percolate through the soil to recharge the aquifer. Rain gardens are a beautiful solution for stormwater management that simultaneously create wildlife habitat, but they only work on sites with adequate drainage rates – remember to perform a percolation test! For more information on rain gardens, read our previous posts (Rain Gardens for Stormwater Management; Rain Garden Case Study).

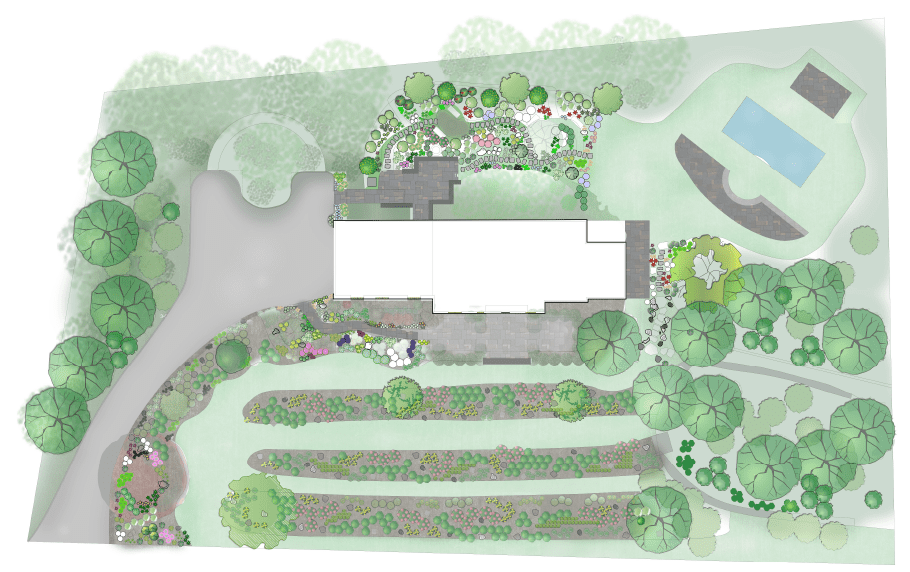

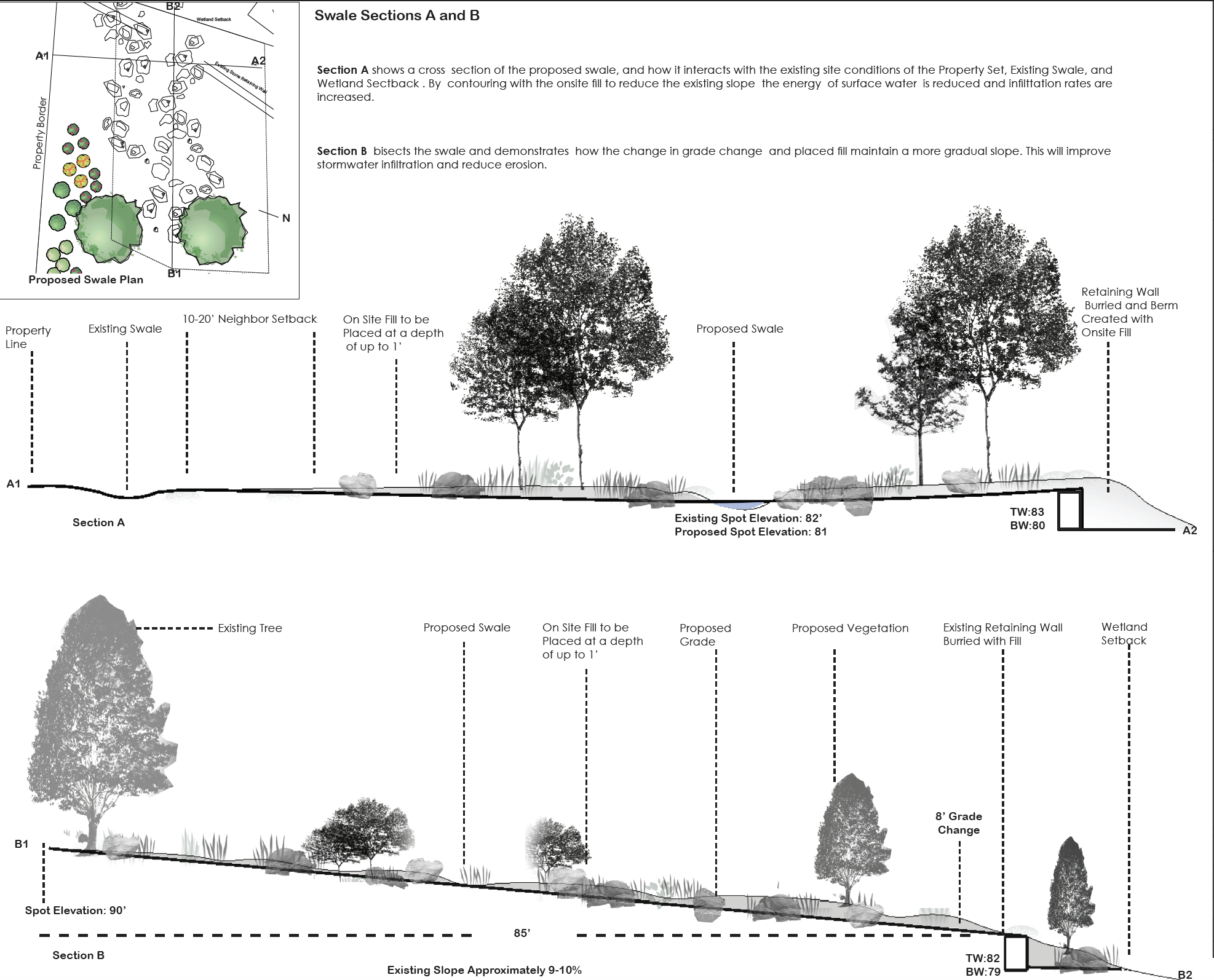

Another landscape drainage tool we frequently deploy are bioswales – stone armored trenches that direct stormwater through a specific path, typically ending in a dry well, rain garden or retention pond. Directing stormwater through a particular path reduces erosion elsewhere. Swales can become stunning landscape features by designing native plantings around it to mimic a stream bank and using a mix of river rock and boulders to create a natural aesthetic. For more information on bioswales, read our case study blog.

If you have a pond, stream, lake or other waterbody on your property, it is critical to protect it from nutrient and sediment loading. We always recommend a vegetative border around most or all of a waterbody perimeter, to intercept stormwater runoff it and filter it via wetland plants, before it contaminates the waterbody. This is especially important if the waterbody is surrounded by lawn that is treated with chemicals. Even an organically treated lawn will still contribute nitrogen and particulates to waterbodies if not stopped and filtered. Lucky for us, native wetland plants are some of the most adept at removing toxins and sediment.

Support Pollinators

A successful pollinator habitat hinges on two elements: the right plants and the absence of chemicals. Plant selection must coordinate a succession of blooms, from late winter to late fall, ensuring an on-going buffet for pollinators. While many native plants support some kind of wildlife, some plants play an outsized role in attracting a variety and abundance of species. Tallamy identifies goldenrod, asters, woodland sunflowers, blackeyed susans as the top keystone plants for lepidoptera (butterflies and moths) and native bee species.

When evaluating whether or not to use a cultivar of a native species, we often consult the trial garden research at Mt. Cuba, where cultivars are compared on a number of features including pollinator visits. (For more information on native plants, see our previous posts GJLD’s Favorite Native Perennials Part One and Two and check out our post about Designing a Bird Sanctuary Part One and Two.)

All the right plants mean nothing, however, if they are covered in toxic pesticides. Pesticides are indiscriminate killers, lethal to all insects that touch them not just those that are targeted. This is especially true of mosquito and tick spray treatments: they don’t work on mosquitos (who fly away) and hard bodied ticks, but they do kill pollinators that feed on contaminated plants. As Roach writes in her article,

What would Doug do about the peril of mosquito-fogging treatments? Skip them. Even fog solutions formulated from natural materials such as pyrethrin aren’t mosquito-specific, he explains, indiscriminately killing monarchs and other butterflies, pollinators, fireflies and more.

If you have a mosquito problem on your property, make sure to remove any standing water which is a breeding habitat for mosquitos. Mosquito dunks, a larvicide that only targets mosquito larvae, can be placed in open catch basins. The most effective mosquito program targets the source, not the broader environment. For more information on organic mosquito control solutions, read our previous blog.

Support a Viable Food Web

Beyond a pollinator habitat, each residential landscape has the potential to support a larger food web – the complicated interactions between wildlife species and what they eat. Upholding the previously mentioned principles – organic landscapes with a succession of native blooms – supports the ground floor of the food web: insects, particularly pollinators who in turn help plant populations reproduce and survive. Your home landscape can also be designed to support birds, who are severely threatened globally, and other wildlife species.

The National Wildlife Fund created standards for habitat creation in their Certified Wildlife Habitat program:

An ideal Certified Wildlife Habitat® provides food, water, cover, and places to raise young for wildlife with a minimum goal of 70% native plants that provide multi-season bloom and are free of neonicotinoids and other pesticides or herbicides.

Food in a wildlife habitat includes pollen/nectar species as well as grasses producing seedheads and shrubs or trees producing berries. Seedheads and berries last through fall and winter, extending the viable habitat to year-round. Water is essential for drinking and bathing; if designing for birds, be sure to include shallow steps in a water feature to accommodate their short stature.

Cover is an often overlooked habitat necessity – it allows species to travel safely from planting to planting without facing exposure to predators. When implementing in a design plan, we aim to create masses of species and to avoid designing landscape areas that are very isolated from other patches of habitat. Instead, we think in terms of repeating groups and creating habitat corridors.

Places to raise young often includes woody shrubs and trees where birds can nest, but also includes plants like sedges and grasses, which can be used as nesting materials.

70% native plants is another unique tenant based off of research that Tallamy’s grad student, Desirée L. Narango, did: “looking at the percentage of native versus nonnative woody plants needed to support a population of chickadees. The figure she came up with was 70 percent native, which means 30 percent nonnative. That is that area of compromise,” says Tallamy.

If there are non-native, heritage plants you can’t let go of, let them be only 30 percent of your landscape, as long as they are non-invasive. Invasive plants displace natives beyond the confines of a cultivated landscape and can be extremely hard to control once released. “Now, you can’t compromise with invasives. They are ecological tumors, so even one is not good,” says Tallamy.

Sequester Carbon

There are three main factors effecting the carbon footprint of a landscape: 1) organic maintenance not 2) cultivating soil microbes 3) abundance of biomass, especially deeply rooted and woody plants.

As mentioned above, organic landscape maintenance is paramount to the survival of pollinators and birds. It is also critical to supporting soil microbial communities. If a garden is fed synthetic fertilizer, the plant gets essential nutrient directly from the fertilizer, instead of partaking in a mutually beneficial exchange with the soil microbes. As the saying goes, synthetics feeds the plant, not the soil.

In an organic garden that is not treated with synthetic fertilizers, but rather has compost added to support soil microbial communities, a crucial trade occurs. Plants sequester carbon dioxide from the atmosphere during photosynthesis, converting the carbon in carbon dioxide into glucose. They then trade this sugar water to microbes in exchange for other nutrients deep within the soil that only the microbes can access and make plant available. When the microbes eat the glucose, they secrete a form of a sticky carbon molecule known as glomalin. Glomalin helps to aggregate soil particles into hummus, and its stable structure transforms soil into a carbon sink, a storage system for carbon from the atmosphere.

To further encourage this relationship, it is imperative to plant a diversity of native plants. Just like plants and animals, soil microbes can also be specialist or generalist. By planting a diversity of plants, we can attract a diversity of soil microbes, and take advantage of their niches within the soil strata, thereby storing more carbon throughout more layers of soil! Deeply rooted plants like native grasses are especially adept at storing carbon deep within the soil and play an outsized role in carbon sequestration. Woody plants like trees are able to store some carbon in their woody tissue, creating another carbon sink, albeit slightly less stable (if the tree burns, the stored carbon is released back into the atmosphere). For more information on soil as a carbon sink, read our previous blog.

What About Lawn?

You may have noticed that nowhere in these ecological tips did we mention lawn. That’s because lawn contributes no ecological benefit to your landscape. In Tallamy’s words:

It’s not just neutral; if you have a good lawn the way you’re supposed to, it destroys the watershed, or at least it degrades it. It’s not supporting any pollinators. It’s not supporting a food web. And it’s the worst plant choice for sequestering carbon. We can do better.

Our landscape designs always include a reduction in lawn – it’s the only way to pack in as much native biodiversity as our landscapes require to reach our ecological goals. When discussing with a client, we always ask – how do you use the lawn here? If there isn’t a good reason, we encourage them to incorporate it into the landscaping. Lawn that must be held on to can be converted it to a no mow lawn that requires far fewer inputs and maintenance.

Inspired to improve your landscape ecologically? Contact us to get started. Now booking summer 2025 designs and installations.